A Thread about Bad Taste

My conversation with author Nathalie Olah, from the first Threads of Conversation live event.

If you follow me on Instagram, you probably saw me posting about something seismic which happened this week. An earthquake of the Threads of Conversation variety, if you will.

About a month ago, I introduced the Threads of Conversation book club. The first book I chose was about the topic of taste - bad taste to be precise (that’s literally the name of the book). Fast forward to last Wednesday, and I’m facing a packed audience at Salted Books in Lisbon, a beautiful English language bookshop run by writer Alexandre Holder, where I interviewed Nathalie Olah about her book, Bad Taste. For those of you who couldn’t be there, here’s a little recap of the night.

Don’t forget to subscribe for more Threads of Conversation. You can also listen to the podcast on Apple Podcasts or Spotify, and follow on Instagram.

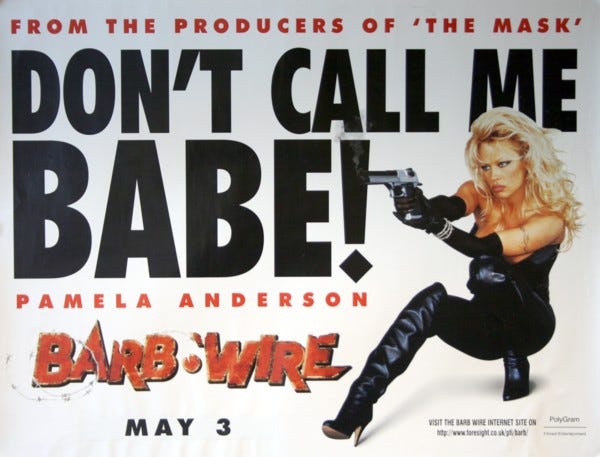

Nathalie began with a reading from the book, a passage where she remembers visiting her local video rental store when she was 7 years old. There, she encountered a poster of Pamela Anderson, advertising the star’s new movie, Barb Wire. “Anderson wore a skin-tight satin and PVC bodysuit and stiletto heels, breasts nuzzled together like the two bread rolls that I carried in a plastic bag from the bakery a few doors down, as she raised her arms to wield a .357 Desert Eagle,” Olah recalls. “[It was] the severity of the image, the polarities of yellow hair dye and black lycra, the cutesy babydoll face rendered severe thanks to the needlepoint eyebrows, lavish winged eyeshadow, and frosted lip gloss that got me… this image presented a kind of freedom.”

The freedom that Olah is talking about is a freedom from the confines of ‘good taste’, a strict social code which keeps us locked in a cycle of class prejudice and consumerism. This is what she explores in her book.

Georgia: Taste is a giant topic. What made you say, ‘Okay, I’m going to try and put this in a book.’?

Nathalie: I'd written a book prior to this in 2019 that was more of a straightforward polemic about the state of cultural production, particularly in Britain, and how it was skewed in favour of a very small, very white, very affluent elite. Whilst writing that book, this question of taste kept cropping up. Because the justification that people used for why they hired particular people and not others was that they grasped taste in a way that somebody else didn't. And so taste seemed to be completely caught up in the question of class representation. A few people that read that book said the bit about taste was interesting, and that they wished there'd been more of that. So I thought, ‘Okay I'm going to write a book about it.’

Georgia: You divided the book into ‘Homes, Food, Fashion, Leisure and Beauty’. Why did you decide to split it up that way?

Nathalie: I was trying to think about our consumer identities and where they show up in our shopping habits, and it tended to be those five categories. The way that you style your house, the way you style yourself. But also the forms of leisure that you take part in, which you now advertise to the rest of the world.

Georgia: In terms of the references you used, how did you choose what to include? Obviously, the more contemporary references you use, the more urgent the book will feel for the current moment. But if you use too many contemporary examples, then the book will age quickly. How did you find the balance?

Nathalie: In the book, I do close readings of scenes from television and film to illustrate some of the points. I wanted each chapter to have a personal element - so either an anecdote or a bit of reported journalism; my own encounter with the question of taste around that particular issue. And then I wanted to look at a cultural artefact - so a scene from cinema or TV, before doing the slightly more theoretical, dense part of the analysis. So each chapter follows that structure. The choice was completely organic and reflects my own interests — these were scenes that I had thought about obsessively over many years.

Georgia: These cultural artefacts range from Axel Vervoord, the guy who designed Kim and Kanye's incredibly minimal, sleek, grey home, to The Sopranos, and the film Blue is the Warmest Colour. Can you pick one of these references and talk about how it fits into the book, and why you chose to include it?

Nathalie: My favourite one is Under the Skin, the Jonathan Glazer film. It’s in the ‘Fashion’ chapter, but you wouldn't necessarily think it's a film about fashion. For anyone who hasn't seen it, it's a very strange film with very little dialogue. It stars Scarlett Johansson, but it's shot in Glasgow and rural Scotland, and a lot of the footage is real footage, not staged. So she would walk down the street and Jonathan Glazer would film her from a distance. But the people she's interacting with don't realise that they're in a film. They don't know that they're interacting with Scarlett Johansson. She's dressed in, like, Primark clothing. But it's still her - no prosthetics, no elaborate makeup. It's quite obviously Scarlett Johansson, but when you put her in normal clothes and walk her down a high street in Glasgow, she ceases to be Scarlett Johansson. And that, to me, was a symbol of how powerful clothing is.

I also think The Sopranos is a really good example of taste politics. They're nouveau riche, but they're new money under the worst circumstances imaginable, because he’s a gangster. There are lots of scenes in which the Sopranos are interacting with their neighbours, the Cusamanos. Financially, Tony’s of the same standing as they are. But he's Italian American, and has a very different aesthetic sensibility to these waspy white Americans.

The Cusamanos tend to soothe themselves quite frequently throughout the show with assurances that they have superior taste. And that's almost the only thing they're able to soothe themselves about, because quite often, when they're having critical conversations, someone will point out that the conditions in which they got rich - the American banking system for example - probably aren’t ethically any more clean than what Tony Soprano's doing. And then they always then make some comment about the way that Carmela chooses to dress, or the way that she styles the home. They reassure themselves that they are better people, that they've got a better moral compass, because they know how to present more respectably than the Sopranos do.

Georgia: Your thesis is that we all think that we have personal taste, but actually our ‘taste’ is a result of capitalism and political forces that we’re not necessarily aware of. After writing this book and thinking about taste so much, do you think there’s such a thing as neutral taste? Is that even possible?

Nathalie: The conclusion I was trying to draw is that there are these very seismic forces that are acting on us in terms of our consumption habits and the ways we behave. And one thing that all of us urgently need to do for many reasons, not least because of imminent climate catastrophe, is think a lot smaller. In terms of my consumption habits, increasingly, things come recommended through friends, or handed through friends, or mended by a friend. This skirt [Nathalie gestures at the skirt she’s wearing] was something that a friend gave me that she said she thought would really suit me. As opposed to me going into these vast corporations and basically being told what to wear. So I think it's more about gathering and having conversations and learning about the world through community, as opposed to the forces of advertising.

A lot of the ideas around what constitutes good taste also have their origins in the religious wars of the early modern period. The conflict between the Catholic and the Protestant Church, and the Protestant Church essentially winning out and conquering America, and becoming the definitive aesthetic code of this waspy North American white elite. So a lot of our ideas of what's tasteful, understated and minimal have their origins there. You tend to find the idea of what's ‘gauche’ is anything that's coded as Catholic historically.

Johnny Pitts quotes Franz Fanon in his book Afropean, saying that ugly will always be defined as whoever is the other. So whoever capitalism fails, whoever it has to define as its other, whatever the aesthetic sensibility that's associated with that group of people, or the behaviours or the preferences or the traditions, they will always be coded as ugly. So it's almost not a visual aesthetic thing. It's a lens through which you look at the world.

Georgia: One of the things I found really interesting in the book is this idea of good taste being essentially ‘clean’ and ‘under control’. Whereas bad taste is associated with the unwieldy, messy and chaotic. It’s funny that you began the book with the Pamela Anderson anecdote, because people used to think she was kind of tacky, but she’s recently had this renaissance in fashion. She’s all over magazine covers, doing campaigns. Firstly, she’s older - therefore she’s desexualised, because past a certain age, women start to fall off in terms of the way society views them. Secondly, she doesn’t wear makeup anymore, thirdly she’s now a vegan. So literally the transformation of Pamela Anderson in the time since you’ve written this book proves your point. That those more puritan qualities are still what society deems ‘good taste’, this sense that she’s more refined and ‘luxury’ now.

Nathalie: Yeah, and what's really interesting about her is the moral arc. Because she was really vilified in the 90s, because she married Tommy Lee really quickly, and she got Hepatitis C from him. She was always characterised as irresponsible, a bad influence on women. She had all these artificial modifications to her body which were seen as an aberration against womanhood. Now she's America's sweetheart and they're like, ‘We love Pamela Anderson, isn't she adorable?’ But I wonder whether if she didn't shun makeup and still dressed as she did in the mid-nineties, whether society would have permitted her to have that moral arc.

Georgia: Another thing I want to ask you about is this idea of two currencies that you touch on in the book: money and time. And how a lot of the things that we consider to be ‘good taste’, are things that were made using time-consuming, ‘natural’ methods, and how these are considered morally better somehow. Can you tell the story about buying gifts for your family?

Nathalie: I thought it was quite interesting to think about how luxury had changed over time with my family. I grew up working class. I'm middle class now. But for my parents and certainly my grandparents, convenience and ease and things getting sped up, that was luxury. They lived very hardworking, time-poor lives. Advanced modern conveniences like the microwave - those were the height of luxury to them. Obviously tastes have evolved since then, but I recalled this time in my early 20s. I'd saved up all my money to buy my family what I considered to be really nice Christmas presents. There's a shop in London called Labour and Wait that sells sort of earthy and homespun homewares. And I was like, ‘Well, that's so chic. I'll buy them stuff from there.’ And just the look of disappointment on their faces when they opened yarn, and old feather dusters. They were like, ‘We've spent the last 50 years trying to get away from all of this stuff. What are you doing bringing this into our homes?’

Georgia: The last question I want to ask you is about the chapter on beauty. You make a definition between beauty, sexiness and romance. Can you explain the difference between those three?

Nathalie: There’s a book by the sociologist Eva Illouz called The End of Love, which I would really recommend if anyone's interested in this. Essentially, she was arguing that there's a distinction between beauty and sexiness. Beauty is something that's always presented as inborn, innate. It’s this ideal that, essentially, advertisers have created, or at least seized upon from art history, and they use it as the thing that haunts us all. This image of a beautiful person that we should all be, but none of us can be. It’s an ideal that we can't ever attain. But the way you get there is through sexiness, and sexiness is something that’s bought. So it's almost like they throw you a bone. You can’t be beautiful, but you can buy ‘sexy’ instead.

You can buy sexy, but it will always be coded as second class. So sexy is never beautiful, according to the logic of marketing and advertising and modern media. And the people that present as sexy are always treated as trashy. And the advertising industry has also turned body parts into commodities, so anyone who just happens to be born with a big ass or big boobs, through the language of advertising is in possession of these commodities. And the more commodified you look, the less beautiful you are.

A big thank you to Nathalie, Salted Books and everyone who came along and asked such great questions. Stay tuned for the next event.

Threads of the week

On my phone I have an album called ‘outfit ideas’. Oftentimes, I’ll screenshot people I see on socials whose look inspires me in some way - either the whole thing, or certain details (is that creepy? It’s purely for styling purposes!) It’s also a great way to get an idea of your own style. After a while you start to see a really clear picture of what you’re drawn to, simply due to the items or elements that appear across multiple images.

Anyways, I can’t remember where this photo came from or who these people are, but I just loved the vibe of the person on the left. Something about the graphic on the back of the tee (the best vintage tees are printed on the front and back - it’s more expensive to print both sides and somehow feels more considered, too) told me that this person cared about vintage tees just as much as I do.

The technical pants have the perfect proportions and construction, and the socks and sandals just looked so damn cool. Altogether effortless, sleek, contemporary-but-not-hypey. Anyways, I didn’t realise how firmly this image had lodged into my brain until I realised today that I was wearing almost the exact same look. I screenshotted that photo in June 2022, so 2 years later, I’ve subconsciously recreated the inspiration. Thank you, whoever you are! I hope you don’t mind me sharing here.

Outfit credits (I’m sure you’ve seen me wearing these bits before): tee is vintage Harley Davidson, bought from a vintage market called Mercado Amour in Lisbon. Technical pants are also vintage, from an amazing Portuguese seller called Daia. The Birkenstocks belong to my boyfriend - they’re way too big, but I weirdly love how they look that way. The lighting in my selfie is terrible so you can barely see the socks (or pants) but they are a ribbed pair of cotton ankle socks from Cos, for a little more texture play.

Loose Threads

Thanks for the love on the Thread about fashion and literacy. Here are two more examples I should have included.

Someone designed a typeface by growing fungi. As we already know, microbes are cool.

I really like this branding. Product is cute too.

Start your own Thread

Add your thoughts in the comments, and let me know whose Threads of Conversation you want to hear next! And if you enjoyed this edition, why not forward it to a friend?