I started modelling back in 2013. My first show season was in February 2014. In September 2013 my agent told me, “If you want to go to Paris, you have to lose a few inches off your hips.”

Over the next few months, I went on a weight loss crusade, reducing my calories to the bare minimum, and undertaking a strict routine of Bikram yoga that saw me spending up to 6 hours in the hot room every week. (In one class, a teacher told us that “sweat is fat crying”.)

At first, I looked fantastic. My skin glowed from all the sweating, and my smiley cheeks hollowed into sharp, photogenic angles. My agents were delighted, congratulating me during my weekly measurements at their office. One of them even started doing Bikram yoga, too.

They sent pictures to an agency in Paris, and I got signed. I’d been living in Sydney and doing cheesy denim commercials, but suddenly fashion week was within reach.

In the lead up to my departure, I kept up the routine, diligently shaving off even more weight. My boyfriend was getting worried, but I shrugged off his concerns. Didn’t he know how important this was for my career?

Every Sunday I’d allow myself a ‘treat day’ where I could eat whatever I wanted. I distinctly remember stuffing down a nutella crepe, despite the fact that I was already uncomfortably full - and I don’t even like nutella crepes that much? It was like a Cinderella game show, eat as much as you can before the clock strikes 12 and you turn back into a hungry pumpkin.

When I arrived in Paris, the agency cooed over my ‘perfect’ body. They sent me off to castings and I started picking up bookings immediately. I found a Bikram studio and started doing classes in French, where the instructor enthusiastically told us to “poussez les hanches, poussez les hanches, pousse, pousse, pousse!”

Outside the hot room, I was living my fashion dreams, whilst subsisting on a diet that involved a lot of black coffee and cigarettes. “This is how you do it,” I thought. “I’m so cool.” A small voice in my head whispered that perhaps this was unsustainable.

I went for test shoots where random photographers took pictures of me in their apartments in high contrast black and white, an aesthetic designed to emphasize bony angles and gaunt, ‘rock’n’roll’ bodies (see also: Hedi Slimane). I stripped down into a nude bodysuit in some guy’s home, because apparently my agency needed ‘bikini shots’.

At show castings, I sat on the floor with dozens of other skinny girls. Everyone talked about their favourite foods and restaurants and what they liked to cook. I later found out that this correlates to a medical trial called the Minnesota Starvation Experiment, performed at the University of Minnesota in 1944.

The study was designed to determine the physiological effects of severe and prolonged dietary restriction. Their findings showed that as the subjects began to starve, they became more and more obsessed with food, talking excessively about it and gravitating towards cookbooks and other food-related literature.

I remember a Russian girl saying loudly at a Dior casting ‘I’m not going to get booked because I ate pizza last night’. She was angrily shushed by an assistant, who was working for the casting duo who booked all the most important shows. They were known for keeping models waiting for hours for no reason, often in windowless rooms with no food or water. Rumour had it they even made models clean up their lunch sometimes, before the castings could begin.

On the first day of Paris Fashion Week, I opened and closed the Jacquemus show. After the show, I found out I’d booked an exclusive for Givenchy, which meant I wasn’t allowed to do any other shows for a week. My agent suggested I was looking quite thin, so I should probably lay off the yoga for a bit. How about just one class? I wheedled, fantasising about the fat crying.

When I got to the Givenchy fitting, the skirt was too big. I’d lost so much weight that I was too small, even for Paris. I was cancelled on the morning of the show, and my look went to another model instead. I had the Chanel fitting the following day, so I shovelled down some cookies in the afternoon, as if that might prevent it happening again. Luckily my look was a large woollen coat, so the fit was fine. Two days later I catwalked through a supermarket filled with fake food.

When I returned to Sydney, my friends were concerned by my appearance. My face and arms had begun to get fuzzy, which happens when your body overcompensates for a lack of fat (I’d cried it all away in hot yoga). I told myself that my periods weren’t coming because I had an IUD, not because my BMI was on the floor.

Because of my success in Paris, every client back home in Sydney wanted to see me. I drove around to castings but didn’t book any jobs, because I looked too scary for the mainstream Australian market. My agent told me it was time to get my ‘commercial body’ back, and that I could return to being skinny for couture. She seemed as obsessed with my weight as I was.

Soon after, I was blind booked on a denim campaign in Melbourne. When I arrived, I could hear the team whispering behind my back. I felt so embarrassed - they’d been hoodwinked by my agents into hiring a skeleton. I looked like a Halloween costume, not a model.

On one job, I got fired on the spot. The designer sent me away after seeing how awful I looked in her clothes. On another, a shoot for an indie brand, I lost my fee because they had to spend so much extra on retouching. The client called my agent and told her she thought I needed help. The whole thing was stressful and humiliating.

Eventually I went to see a dietitian, who put me on an intense calorie gain plan. She told me I needed to reboot my metabolism or risk messing it up forever. I followed her orders, and essentially went on a sanctioned binge for a few weeks.

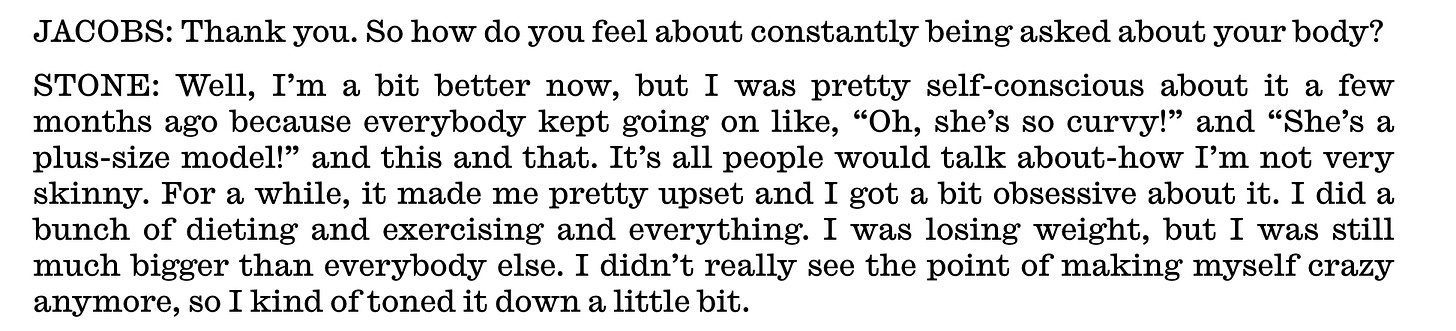

At first nothing happened, then suddenly my cheeks filled out and the weight jumped on. On one shoot, the stylist was visibly shocked by my newly round face, and taped my temples to give me cheekbones again. My agents panicked and told me to stop seeing the dietitian. She said if I didn’t continue on her plan, that my weight would nosedive again, but that eventually my metabolism would permanently slow down, leading to long term weight gain. I was caught in a tug of war between these outsiders, all of whom wanted control of my body.

Then, it was time to go back to Paris for the couture shows. I stayed with my agent, who leased me his own bedroom for an extortionate price, whilst he shared his flatmate’s upstairs. I lay in bed feeling miserable and trapped, hearing their murmurs in the room above.

My four-year relationship was also breaking down, not helped by the fact that I was about as attractive as a table leg. The energetic, charismatic girlfriend who loved beers and ice cream was now a fuzzy, sad, lonely girl in Paris. My weight slid back down again. My face stayed round, though, something my agent commented on. Now I had the worst of both worlds - my body was too thin, my face was too fat. I couldn’t do commercial work, but I didn’t have the angles for editorial either.

By now the story begins to tell itself. I stayed on the rollercoaster for a while, before deciding to sort myself out once and for all, after a model I knew got diagnosed with early onset osteoporosis. The dietitian had warned me this could happen - body fat produces estrogen, and estrogen is what maintains bone density in women. Without it, your bones become brittle and break.

Writing this account, I feel very emotionless. I no longer relate to that version of myself, and I rarely talk about this phase (like certain unpleasant public figures, I think that airtime often gives these things more power). I also don’t want to suggest I’m any kind of example, nor trigger anyone with the details of my experience.

But occasionally, I feel very angry about it all. Opening up Vogue Runway to look at pictures from fashion week, and seeing the same twig limbs sticking out of all of the clothes, just like 10 years ago. When I click on the ‘details’ shots and can see the downy hair on models’ arms and shoulders. Hearing designers talk about ‘the woman’ when what they actually mean is ‘the 12-year-old girl’. (It’s giving Humbert Humbert, guys). When people say things like “yeah, but they’re naturally that way”. (Some are, but most are on a diet, or haven’t hit womanhood yet).

I have seen a few models I know from ‘my era’ suffer the consequences that the dietitian told me about. Their metabolism slowed down and caused them to gain weight. I’ve heard stories of peers who have fertility issues from remaining thin for so long.

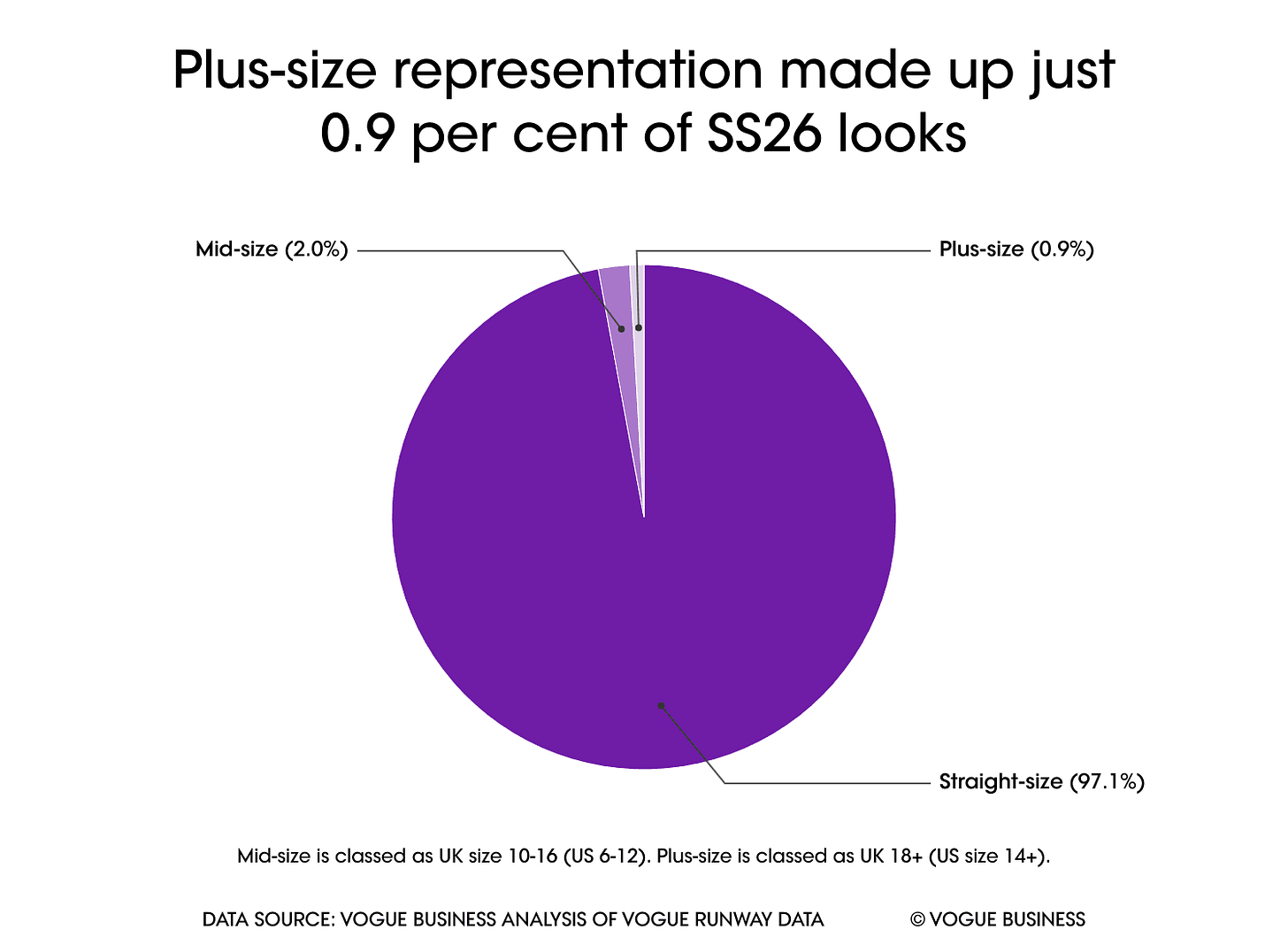

I wish casting directors spared a thought for these things when deciding their ‘look’ of the season. (And no, putting one plus size model in your line-up isn’t progress - it’s tokenistic and humiliating for the model in question, and highlights the lack of size diversity elsewhere).

Perhaps this is all a rant, but I thought that now might be a useful time to share this story. After a season where models, once again, seem to disappear amongst the clothes - maybe this will give a little insight on what actually goes into maintaining this ‘aspirational’ body, and the long term effects of this type of beauty standard. Especially as it bleeds from the runway into real life via GLP-1s.

I’m not trying to corral sympathy, nor suggesting I’m representative of ‘normal’. I’m aware that even at my natural size, I am a slim person. Rather, if someone like me, and many of the models I met (all of whom fit neatly into society’s beloved boxes) have to do this for fashion, then what message does that send more widely? As women, we deserve better.

Have you listened to the Threads of Conversation podcast? You can also find it on Apple, Spotify, and YouTube. You can also follow Threads of Conversation on Instagram and TikTok. Subscribe below for more podcasts, essays and interviews.

It really shouldn't be like this. Thank you for letting us look behind the curtain of the fashion industry. Harrowing. Also, women's bodies truly are so beautiful, if designers can't make their clothes look good on an ordinary/not skinny body - are the clothes really that well made?

It’s weird how “aspirational” has been coded as “anatomically barely possible” by the fashion industry. It has nothing to do with making money. It seems to be more about surfacing all the nastiest biases and sexism that lurk in culture as a thing for consumers to chase. And models are caught in the middle.

Thanks for writing this, it’s important.